“Disability” has become a dirty word in our society. We are conditioned to believe that anything that slows us down from the rat race of modern life is something to be lamented.

We have laws and practices in place to “accommodate” such disabilities to ensure a fair shake for all, but these are formalities that are government requirements, not mindful ways institutions deliver health to their employees or students (because apparently a requirement is the only way to get most places to recognize, accommodate, and help people succeed in health and career).

But is it fair when we stigmatize those who cannot perform to our ridiculously high standards, making them feel less than worthy?

Are those with “disabilities” actually worse off? Or are they the very ones we should all look to for guidance on healthy lifestyles?

I propose that many of the disabled are actually some of the most able of us all.

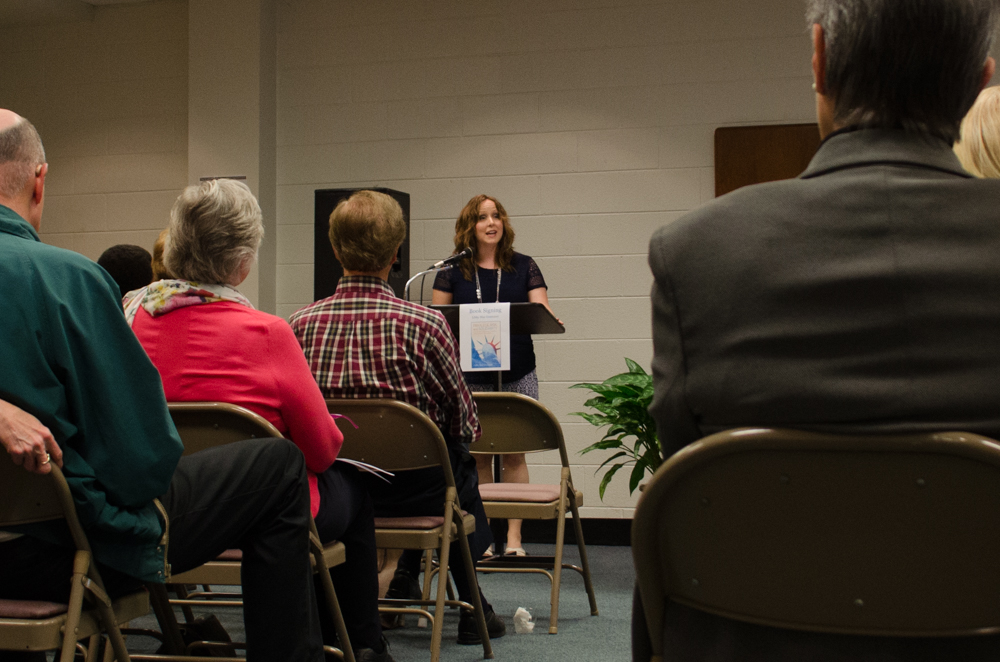

Recently, I had to prove myself “disabled” in order to balance my grad school life and home/work life. I was required to submit copious documentation and pour out my psychological history to multiple levels of the university, just to get a break on three course credits.

Now, to be sure, graduate students are some of the most ratty racers on the planet. They have more to do than most other jobs combined. Their work never stops – they’ve never read enough, written enough, presented enough. And they choose this lifestyle. I chose this lifestyle.

But I didn’t choose to be predisposed to anxiety and depression. And I cannot go back and change my history to remove those things that exacerbated the symptoms of my disease. I can only treat my condition with therapy, medication, and healthy lifestyle choices. I can only accept my “disability” and do my best to keep up with the ridiculous standards for graduate students (built by the male, monastic hierarchy of old).

In treating my disability, I must attend biweekly therapy sessions and take daily medication to relax and to sleep. I must eat a balanced diet, avoid alcohol (especially more than one serving in a given sitting), and exercise as often as possible. Otherwise, I am miserable, depressed, and anxious about every little thing. I lose my focus, my mojo.

And my focus and mojo are what make me a great student. My tenacity and determination and creativity are my strengths. These are the non-negotiables in my careers as a student and a paralegal and a minister.

Most graduate students struggle to keep a balanced lifestyle. Unless they come from copious amounts of money and/or have a huge nest egg or sugar daddy/mama (ha!), they are poor, strained, and it’s a daily struggle to remember to eat at all, much less eat well. And working out? Well, that’s a tough one – when do they have time to put down the books or get away from the computer?

My disability insists I be more healthy. It reminds me daily of the need to take time with loved ones (and not create the “graduate widow(er)” at home). It makes me so aware of my happiness, my priorities (faith, husband, family, school – in that order). It makes me sleep 8+ hours every night. It makes me eat well (and fights me hard when I don’t). It restrains my indulgences and keeps me dedicated to my regimens, and it lets me off the hook from those regimens when they rule my life too much.

My disability is my strength, not my weakness. And anyone who sees my need for reduced course load as a weakness (“you’re just not cut out; you can’t handle the pressures if you’re this overwhelmed; you aren’t good enough for this program, or any grad school”) is simply uninformed about what a disability is.

The disabled are the strongest, most determined people. They fight their own illnesses and limitations daily, make the tough decisions to get accommodations in the face of academic or other stigmas, and they still succeed in what they do – sometimes further than the able-bodied in the programs. Yeah, they may take a little more time. Yeah, they might need to take different kinds of courses or work through different programs to finish their work in other ways. They might even take a break and tend to their disability for a few weeks or months or years.

But they will finish, in spite of all that. And they will be the same amount of smart and successful as anyone else in the program. And they will have done it against all odds. And they’ll probably do it in a much healthier way – in mind, body, and spirit.

So before you throw around the “disability” word as some kind of insult, remember that we “disabled” are some extremely hard workers who overcome more than most “regular” folks ever will. We’re superstars, and we’re just as amazing and intelligent as anyone else in our field, perhaps more so in some ways.